|

Antonietta a.k.a. Tognina Gonsalvus along with her sisters, Maddalena and Francesca, found favour as marvels in the courts of sixteenth-century Europe on account of their unusual hairiness. In an age of miracles and discovery, the novel and the exotic were viewed as demonstrations of divine wit and inventiveness. As such, a hirsute family at court could be justified as a show of piety, and a series of portraits in courtly attire suggest that the Gonsalvus family came to enjoy a measure of privilege and regard. Influential scholars such as Ulysee Aldrovandi were also drawn to the hirsute family, producing several works on paper and woodblock illustrations of the sisters, particularly Tognina. Bolognese Mannerist, Lavinia Fontana, also painted a courtly portrait of Tognina from life, that now hangs in the Château de Blois, France.

Antonietta/Tognina’s father was captured as a child and brought to King Henry’s court from the Canary Islands. The islands' original Latin name, Insula Canaria, actually means the Island of Dogs, the birds taking their name from the islands, not the other way around. The inhabitants were believed to have worshipped dogs. For more information on the Gonsalvus sisters, see Merry Weisner Hanks, The Marvelous Hairy Girls, Yale University Press, 2009. Maddalena, Antonietta and Francesca Gonsalus/Gonsalvus were celebrated in sixteenth-century Europe for their extreme hirsutism (excessive hairiness), a condition inherited from their father who was captured as a child on the Canary Islands and brought to the French court of Henri II. Portraits of Maddalena (also known as Madchen or Madeleine) and her family hang in Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, giving rise to the name Ambras Syndrome for congenital hypertrichosis. Maddalena also appears in the compendium Monstrorum historia by naturalist Ulisee Aldrovandi (1522–1605), as well as a zoological compendium by Flemish artist Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1600) and a miniature commissioned by Rudolph II of Austria.

Where twenty-first century popular sensibilities relegate the display of hirsute individuals to the ‘lowest common denominator’ realm of the freak show and tabloid exploitation, the sixteenth‑century Gonsalus family was seen as properly belonging among the privileged and educated audience of Europe’s courts.The regal dress in the various portraits suggest that the Gonsalus sisters came to enjoy a measure of privilege and regard; Duke Ranuccio Farnese, for example, is believed to have bought a house in Parma for Maddalena’s dowry when she married in 1593. In 2009, the sisters became the subject of the biography, The Marvelous Hairy Girls, by Merry Weisner-Hanks. Hayao Miyazaki’s 1997 feature-length animation, Princess Mononoke (Monster Princess), is one of Japan’s most popular films of all time. Set in the late Muromachi period (late sixteenth century) the abandoned San is raised by wolf gods and vehemently identifies herself as a wolf, going on to champion the wilderness in the forest gods’ battle against encroaching industrialisation. Claire Danes provides the voice for San in the English-dubbed version of Princess Mononoke.

The trial of Lindy Chamberlain in the early 1980s polarised Australians and continues to prick the national conscience. The media demonisation of the bereaved mother, who maintained that a dingo stole her baby, shares a number of striking parallels with witch-hunts from the early modern period, an era in which the ability to transform into a wolf was considered proof of witchcraft. Lindy’s ‘fringe’ religious allegiance to the Seventh Day Adventist Church qualified her as a heretic (a pre-requisite for early modern witchcraft) in the popular consciousness, and insinuations of child sacrifices in the wilderness echo the accusations of diabolically driven infanticide that accompanied lycanthropic court cases in earlier centuries. Uncannily, prosecutors in werewolf trials also argued that the children's clothing had been too neatly removed for a 'natural' wolf to have done so. Media condemnation of Lindy’s ‘insufficient’ emotional response to the loss of her child harks back, perhaps most poignantly, to early modern beliefs that witches were unable to cry when hurt. At the time of the trial, Lindy received a letter from a 'sympathiser' who said he believed that a dingo stole Azaria, albeit a two-legged dingo, like her.

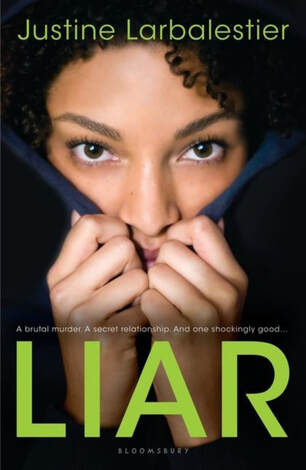

Micah Wilkins, the complex, damaged and maddening (anti) heroine of Justine Larbalestier’s 2009 novel Liar is decidedly undecided, stuck somewhere in between black and white, girl and boy, human and wolf, mad and sane, dangerous and safe. She’s half of everything, especially everything else.

In June 1980, the twenty-eight-year-old East London barmaid Sandie Craddock was charged with stabbing her nineteen-year-old co-worker to death. Presented in Craddock’s defence were diaries and institutional records documenting years of violent outbursts following a cyclical pattern. Her lawyers argued that the true culprit was Craddock’s pre-menstrual tension (PMT, a symptom of premenstrual syndrome, PMS), which “turned her into a raging animal each month and forced her to act out of character,” leaving her with little memory of her actions. The barmaid walked away from a manslaughter conviction with nothing more than probation and a court order to take progesterone supplements, successfully having argued diminished responsibility due to extreme PMS. The following year, having changed her name to Smith, she was before the courts again, this time for threatening a policeman with a knife in Islington. Once more she was released on probation.

Craddock-Smith and premenstrual syndrome were catapulted into the tabloid spotlight, unleashing a flurry of headlines such as “Premenstrual Frenzy,” “Dr Jekyll and Ms Hyde,” “PMS: The Return of the Raging Hormones,” and “Once a Month I’m a Woman Possessed.” Articles were peppered with phrases such as “the monthly monster, ” the “menstrual monster,” the “inner beast,” and “raging beasts.” New York filmmaker Jacqueline Garry credits the media headlines with her inspiration for her heroine, Frida Harris, in the 1999 film, The Curse. The film sees normally mild-mannered “doormat” Frida transform into a homicidal, lupine femme fatale when her period is due (corresponding with the full moon), waking to find that the blood on her sheets is not always her own. The cult Ginger Snaps trilogy draws from a broad spectrum of werewolf lore to chart the tribulations of teenage sisters, Brigitte and Ginger Fitzgerald. The first film casts the werewolf as a metaphor for the coming of age, directly linking the werewolf's lunar cycle with the female monthly cycle. Ginger is bitten by a werewolf on the night she begins menstruating, setting in motion a series of progressive changes to her body, appetites and behaviours.

The first sequel sees Brigitte form an unhealthy dependency on the wolfsbane that initially promised to cure Ginger of her werewolfism. Brigitte finds herself committed to a psychiatric ward, as the film teases out historical links between lycanthropy and notions of lunacy and antisocial behaviour, tackling themes of narcotic addiction, self harm, alternative sexuality and delusion. The final film in the trilogy returns to Canada's colonial past. Early modern histories of misogyny and witch hunts from Europe intersect with the totemic beliefs and practices of the nation's first peoples. |

Who's WhoLearn the stories behind the hirsute faces in the Girlie Werewolf Hall of Fame ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed